Welcome to another issue of Global South Shoutout, the newsletter where we showcase the talent and creativity of people from the global south. Today, we are excited to introduce you to a game that is sure to get your imagination running wild, Here, There, Be Monsters! This game is the brainchild of Wendi Yu, a Brazilian creator who has managed to craft a world that is both terrifying and exhilarating. She describes herself as “a tranny by skill, a Brazilian by chance, and a monster by trade”, and we are sure to find such a rich background transpire into her work!

Here, There, Be Monsters! is set in a world where monsters, anomalies, magicians, and other odd beings exist on the fringes of 'normal' life. These individuals gather in the shadows to live their lives, but they are often hunted and exploited by those who fear or seek to profit from them. In this game, players take on the roles of a diverse crew of monsters, fighting against those who would use or destroy them.

The game has a unique premise and gameplay that will keep you on your toes. But don't take our word for it, let's hear from the creator of the game.

The premise of 'Here, There, Be Monsters!' is such a unique take on monster-hunting media. What inspired you to create a game from the monsters' point of view?

I’ve always had a complicated love/hate relationship with monster-hunting media, and Urban Fantasy in general. I usually love the aesthetics, the tropes, the archetypes, the clichés. Even if most of it is usually bad. They’re just full of possibilities for exploring things like the awe and cruelty that can be found in our cities, how normality can hide all kinds of weirdness, the constitutive relationship between Humanity and Otherness. The idea of a whole underground world existing in secret, masquerading from the ‘normal’ world, is obviously appealing for me, as a queer person. I love monsters, weird artifacts, eldritch tomes, ancient knowledge, occult societies, all that shit, and I love stories about the people who gravitate around them.

At the same time, I hate how conservative most of those stories end up being, intentionally or not. The BPRD, the SCP, the X-Files, the Men in Black, the whole “Occult Detective” archetype, they’re functionally cops. They exist to defend the status quo, upkeep normalcy, and protect the World from the anomalous. There may be some complexity here and there, but their monsters are usually meant to be destroyed, contained or, sometimes, when they’re more sympathetic, cured or maybe studied and explained. As someone who’s seen as abnormal by the status quo, who’d have to be destroyed or ‘contained’ in some places and ‘cured’ in others, whose body is constantly subjected to the scrutiny of ‘curious’ eyes, that bothers me. I’m a monster, not a cop, and I know who my people are.

But even stuff that comes from the monsters’ point of view, like the World of Darkness games, often subscribe to a normative idea of humanity/monstrosity (especially when it comes to physical monstrosity) anyway. Even when the monsters are supposed to get our sympathy, it’s because the twist is that they’re just ‘human like us’ and ‘humans are the real monsters’. In the end, that’s not only politically bad, it’s boring. I’m terribly exhausted by stuff that always end up coming to the same conclusions over and over again.

Monstrosity has been used as a metaphor by marginalized people for ages (I just wrote a subchapter about it in my thesis, for example), and there’s a reason for that. Monsters de-monstrate (not a pun, same root) the limits of the Natural and the Human. They’re freaks, mistakes, deviants, degenerates, horrifying offenses against the natural order that can embody every kind of threat to normalcy. They represent lots of things simultaneously, but because of that they end up transcending meaning: they can hit you straight in the places where language cannot even reach. They’re scary and alluring at the same time. They can make you puke, give you chills, get you wet. Even when you “don’t notice” it. Like when you clutch your purse and cross the street. When you want to “protect” “kids” from “groomers”. When you refuse to touch someone because “what if you catch it?”.

Monsters, as abnormal and unnatural, can destabilize the illusion of normalcy, as living reminders that “natural” is itself a cultural formation; that “normal” is not all that one can be; that there can be much more to life beyond “just the way things are''. So there’s power in reclaiming our monstrosity. We can turn that into a weapon and armor.

So I made the game as an attempt to make something out of those stories that I love, while confronting that genre’s internalized problems, as an exploration of those ideas of monstrosity. Monstrosity here is related to all kinds of marginalization. I wrote it from my experiences as a trans woman from America Latina, but it’s not just about people like me. It’s about every single person who’s made to feel as if they're wrong, weird, abnormal. It's a celebration of being an anomaly and refusing to assimilate, of trying to cherish our weirdness and band together to protect each other – instead of acting like cops. Fuck cops.

You state that the game is explicitly anti-fascist and anti-capitalist. How did you incorporate those themes into the game mechanics?

This is a huge question, isn’t it? Can a game even be anti-fascist and anti-capitalist? I usually think (and my thought on those matters varies a lot) those are things you do, not things you are. Anti-capitalism and anti-fascism, like being against all other kinds of oppression, is a daily practice. It’s an ethos, it informs your actions. I think, in that way, this game definitely tries to be anti-fascist and anti-capitalist in all its aspects, including mechanics, because all of them were created following that ethos. If it succeeds, like a Judge from The Awards said in their commentary, is up to the readers, players and critics.

Also, I tell corporations and bigots to fuck off and die in the first page, if that counts.

Regarding the mechanics, specifically, I believe they always need to work in relation to whatever the game is about. They need to help guide the conversation between designer/game-as-written and players/game-as-played towards the ideas that the game sets out to explore. This is a game about people/monsters fighting back against those who would control or erase them. The biggest “rule”, then, is “do whatever you want and deal with the consequences”. That’s it. All the rest is about choice, not control. It’s trying to give players tools, options and guidance so they can have fun and maybe even some catharsis together, without ever assuming the authoritarian voice of telling them what to do. That’s one of the reasons for such a casual tone in the writing, for example. The 100 backgrounds were about that, too: giving them plenty of choices, and using it as an opportunity to build the world through the monsters themselves.

The game encourages players to create their own supernatural underworld and abnormal gang. Can you tell us more about the collaborative worldbuilding aspect of the game?

The game gives you seeds of a world, but you get to populate it however you want, because who am I to tell you what’s gonna be more interesting to your group. And you do it together, because you’re playing together. For example, you start the game with a manifesto, which is a collective list of anything anyone wants or doesn’t want the game to have, which I stole from Ben Robbins’ Microscope’s palette, and guides the tone and content of the game.

You then create your group of monsters and its Haven together, everyone contributing with the creation of (hopefully important) NPCs. It does have a “referee”/“storyteller”-like job, called the organizer in the book (as in, like, union organizers, but also because it’s the person who organizes the adventures), because I wasn’t too familiar with GMless games when I started designing it. But the text makes it more than clear that it’s a non-hierarchical position, and everyone has equal say in building the story together – I suggest talking it out or flipping a coin in case of disagreement, for example.

The game features 100 pre-made character background options. Can you give us an example of one that you find particularly interesting or unexpected?

The one people talk about every. single. time. is the Werewolf. Even a Judge from The Awards started their commentary with it. It’s a powerful image, to be sure – a BDSM transmasc leatherdyke werewolf biker full of dildos strapped to their limbs, the beast riding their human body as the human rides their bike – and it’s my favorite of Lino’s pieces for this game. I think it resonates a lot with queer experiences. It’s rageful, transgressive, and at the same time, drawn with such a deep sensibility.

On my side, I’m really proud of how the Possessed was received by people with disabilities (it was initially inspired by my mental issues), and of being able to include so many elements of Brasilian mythology.

The game's categorical inclusion of queer themes is notable. How important was it to you to make sure that aspect of the game was front and center?

To put it succinctly, I just couldn’t make it otherwise.

I’m trans in Brazil, the country which kills those like me the most in the world. If I can choose, I don’t wanna hide: I wanna be loudly and proudly and violently a tranny.

It’s exhausting how often the liberal, United-Stater version of ‘identity politics’, completely unrelated to our Global South realities, seem to hijack marginalized people’s struggles for actual change. I’m talking about that whole genre of ‘you are valid’ platitudes, that ‘we’re all human, we’re all equal’ attitude; and also about respectability politics, that whole “good representation”, “no kink at pride”, “[whatever reclaimed word] is a slur” internet discourse. The idea that the end-goal of politics should be representation and assimilation, being included as normal in the system.

Fuck that. Being assimilated, becoming ‘normal’, means we’re accepting this whole machine that marginalizes not only us but countless other lives in countless different ways. The real goal is to destroy those systems of oppression. All of them. No one is really free until everyone is free. So I wanted the game to be as loud as possible about it. Because I could. And because I had to.

The use of magic in the game is quite singular. What inspired you to use this approach, and how does it work?

I dislike the whole “hard magic” thing we see in a lot of contemporary Fantasy media. I don’t even like the idea of “magic systems”. Most of all, I hate what we usually call Vancian Magic. They turn Magic into just another instance of euro-modern Reason; the kind of thinking that’s at the root of, for example, racial categories and the gender binary. I think Fantasy should strive for freeing the imagination to come up with new worlds, not solidify the idea that this one is all we can get. But we don’t even need to go that far, really. It’s just really boring. With that kind of Magic the extraordinary becomes something that can be analysed and predicted. There’s no room for awe (also the term “hard magic” was created by a millionaire writer who gives 10% of his income to an infamously queerphobic religious organization while pretending to be an “ally”, so let’s just stop using it already).

But this is a game that features Magic heavily. In a way it is about Magic, and how some people try to control it, tame it, cage it – like turning it into hard magic. As I said, I design all game mechanics to work with the game’s themes. The way magic acted here, then, couldn’t possibly feel restraining to the players. It also needed to translate the mysterious, chaotic way that Magic appears to the characters inside the (seed of) worlds I planted in the text. It needed, in short, to be about choice, not control. But it also needed to help players, not transfer the whole design job to them.

So, a freeform magic “system”. Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law, and all that. One of the things that led to this game was trying to make Mage: The Ascension work for me, after all. I started with the idea of exchange: Magic as a kind of cosmic harmony, like music is a kind of cosmic harmony. Like even Math is a kind of cosmic harmony. You give something of personal importance, you get to try and do something extraordinary. But it may go wrong, because harmony does not mean order, it still has space for chaos.

To be a Magic User, you give one of your tags and turn it into a reason why you’d be able to use it. To cast a spell, you just need to bet something, anything, even your tags, according to how important it is to you that the spell goes right. If it goes wrong, you keep whatever you wagered. If it works, you lose the thing, or it comes back weird, depending on the dice roll – again, harmony and chaos.

Apart from this general spellcasting guidelines, being a Magic User also gives you a choice of 1d4 Magic Words, representing things you’re more proficient with, spells you’re more used to casting (it also gave me a way to have a kinda unified mechanics for monsters’ abilities, which are pretty diverse in the backgrounds). You can use those words however you want in a spell, how many you want, explaining how they connect to the intended effect, and each word will give you an extra die to get it right, because Magic likes wordplay. Also because of that, puns are not only allowed, but encouraged. Like, you can use the word “root” to cast a spell related to someone’s ancestry, or the word “wreck” to break a lock or get drunk or something.

The reason I emphasize wordplay is, again, a question of choice/control: Magic is not restrained by the normative limits of language, it wants you to be creative, to do more with what you have. Just like queerness, in a way.

Considering all the different influences you had, how did you decide on the game's resolution mechanics, and what do you think it adds to the game experience?

Oh, man… That was hard. The core mechanics were decided from the start, I knew they were gonna be basically the same as my previous game: 3 kinds of tags + advantages or conditions. But since this was way bigger I kept going back and forth, adding stuff, cutting stuff. Many weirder backgrounds have their own gimmicks, for example, some variation of the base mechanics that give them some unique flavor – my favorite is the Vampire, which can be summed up to “if you drink blood you can do vampire stuff”. That’s one of the things I think it adds to the game experience: it’s not prescriptive, it’s just there as guidelines to help the players.

I used to spend a lot of time on the FKR Collective server – “used to” only because I took some time off social media to focus on my thesis, but they’re still awesome, I didn’t leave or anything – and it has left an important mark on how I approach the design of my games. I think in a way my biggest influence was the FKR, which is more like a design sensibility than anything that can be easily defined. Some say it’s about “rulings, not rules”, others that it’s about rules-lite games. For me, and I’m not saying that applies to everyone and every game, it means mechanics should be tools, not rules. They need to help the game somehow, not get in its way or become its focus.

So I took what I wanted from my influences and trimmed it down until I had what I felt was just enough. Then I started adding what I thought would be more interesting options for the player to have, instead of rules for them to learn, like the Haven or the backgrounds gimmicks. I think in the end, all the mechanics work towards allowing the players to have agency and to explore the themes the game sets out to talk about.

The game includes optional long-term mechanics with a focus on character arcs. What can players expect from those mechanics?

I’m a screenwriter, and I thought of those while procrastinating when I should be writing a TV script. There are all those “rules” we learn in writing classes about character development, but, just like I see game mechanics, they’re just tools, not actual rules. Then I realized those tools could be useful in a situation where character arcs need a little more structure, like a game campaign. So I adapted the wants, needs and beats mechanics from screenwriting jargon to provide the “advancement” for the characters, but focused on their actual lives, not boring stuff like stats.

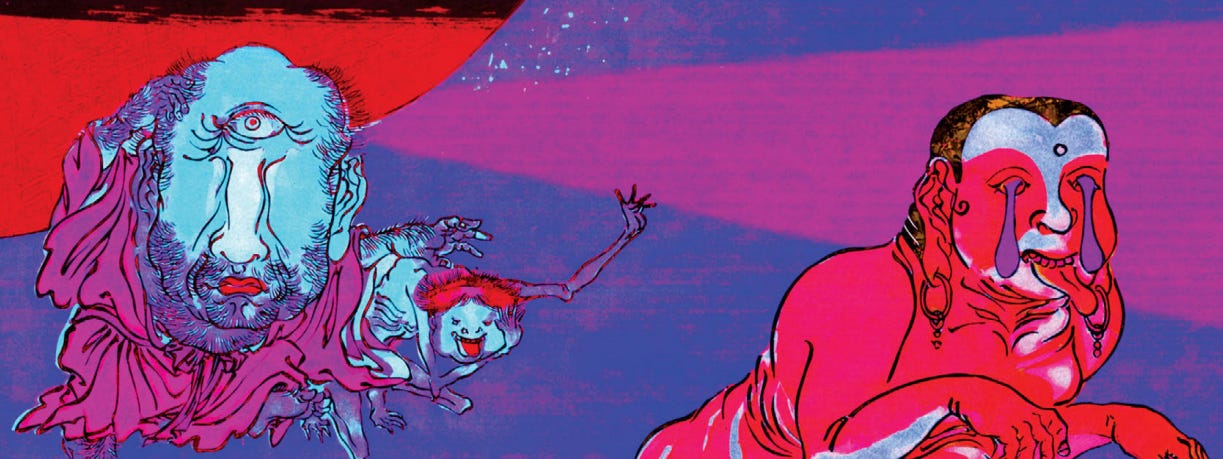

The game is intensely illustrated and has a very colorful layout. Can you tell us more about the design choices you made and why you felt they were important?

First of all, that’s how I like it. I don’t wanna make something for myself if I can’t have fun making it. It’s supposed to be beautiful for me to look at.

But it’s also important to me because it means those characters aren’t trying to hide. They aren’t afraid of being cringe, they aren’t policing their tone, they aren’t worried about being too loud, or too anything. Leave that to the normies. They’re not ashamed of showing their colors, their extravagance, their excesses, their monstrosity. Each of them is unique and weird and beautiful in their own way, and that’s how I wanted the book to look. Like a deranged punk queen.

Lino’s art is just uniquely appropriate for that. Working with him was a dream come true, something I’ve wanted since I’ve read his graphic novel Monstrans. The way he portrays monstrosity is exactly what I also had in mind: not about making the monstrous beautiful, but showing the beauty of it. It’s exaggerated, excessive, sometimes bordering on the ludicrous, and it’s done with such a loving sensibility.

What do you hope players will take away from their experience with 'Here, There, Be Monsters!'?

Someone (I always think it was LeGuin, but it wasn’t her) said art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable. That’s the best I can hope for. That, if you’re monstrous like me, you find some comfort in this, even if just as a fun and cathartic power fantasy. And if you’re not, that it in some way helps you hunt the monster-hunter inside you and embrace the beauty of monsters.

How do you see this game evolving in the future, and what kind of content do you have planned for it?

I have a kind of “DLC” planned for it, but I need to finish my thesis and a couple other projects first. But it’s meant to be all about extra, optional stuff: extra backgrounds and factions that had to be cut, along with more tools for play, like Haven advancement mechanics, more collaborative creation tools, ideas for GMless play, that kind of thing. I hope I can start writing it this year, but we’ll see.

What other projects are you working on that readers can look forward to?

Right now I have no time in my life except for finishing my thesis. Afterwards, which is supposed to be at most by the end of the semester, the immediate next thing I’m writing is a Horror novella, my first fiction in English that I actually want to publish. Apart from the “DLC” I talked about, I have a couple personal projects lined up, like a cosmic horror vs mecha game I’m making with some friends, and I also got a few invites to write for hire, so we’ll see how it goes.

Where can readers find out more about 'Here, There, Be Monsters!' and your other creations online?

They can get the game directly from the publisher at https://soulmuppet-store.co.uk/products/heretherebemonsters, and find my other creations on my itch page: https://wendiyu.itch.io/

My portfolio and CV with all the rest of my non-TTRPG work (I contain multitudes!) can be found at https://wendiyu.carrd.co/

And they can always hit me up on twitter @wen_di_yu, though I’m not sure when I’ll see it these days.

Thanks for reading this edition of Global South Shoutout! We hope you enjoyed learning about "Here, There, Be Monsters!" and the talented creator behind it, Wendi Yu. Don't forget to share this newsletter with your friends and follow us for more exciting content. We'll be featuring more incredible artists, writers, and game designers from the Global South in the future, so stay tuned!

I picked the right day to start following, this game sounds awesome and I'm picking it up.